CARE

FOR WOMEN

VETERANS

Strategy and Design to help women veterans to establish a stable sense of self when transitioning into a non-military environment.

Year

2019

INTRO

After leaving the military, women veterans go through the same transition system as men and proceed to engage with the civilian community. However, women now make up approximately 10 percent of the current veteran population, the fastest-growing demographic. The number of female veterans treated at the VA almost tripled between 2000 and 2015. As a result of this rapid growth, the VA experienced difficulty meeting the clinical needs of female veterans at all sites of care. Additionally, the existing gender specific facilities/services is either barely functioning or non-existent throughout the system of care. These deficits manifest at various points of the journey of women veterans. However, the issue is being highlighted by a number of Women Veteran run Veteran Service Organizations(VSO’s). These VSO’s are engaging with the system to address the concerns of women veterans in the areas of job procurement, assistance with childcare, assistance with procuring homes, addressing physical and mental health issues that are gender specific.

︎︎︎ how might we help Women Veterans to establish a stable sense of self when transitioning into a non-military environment?

RESEARCH

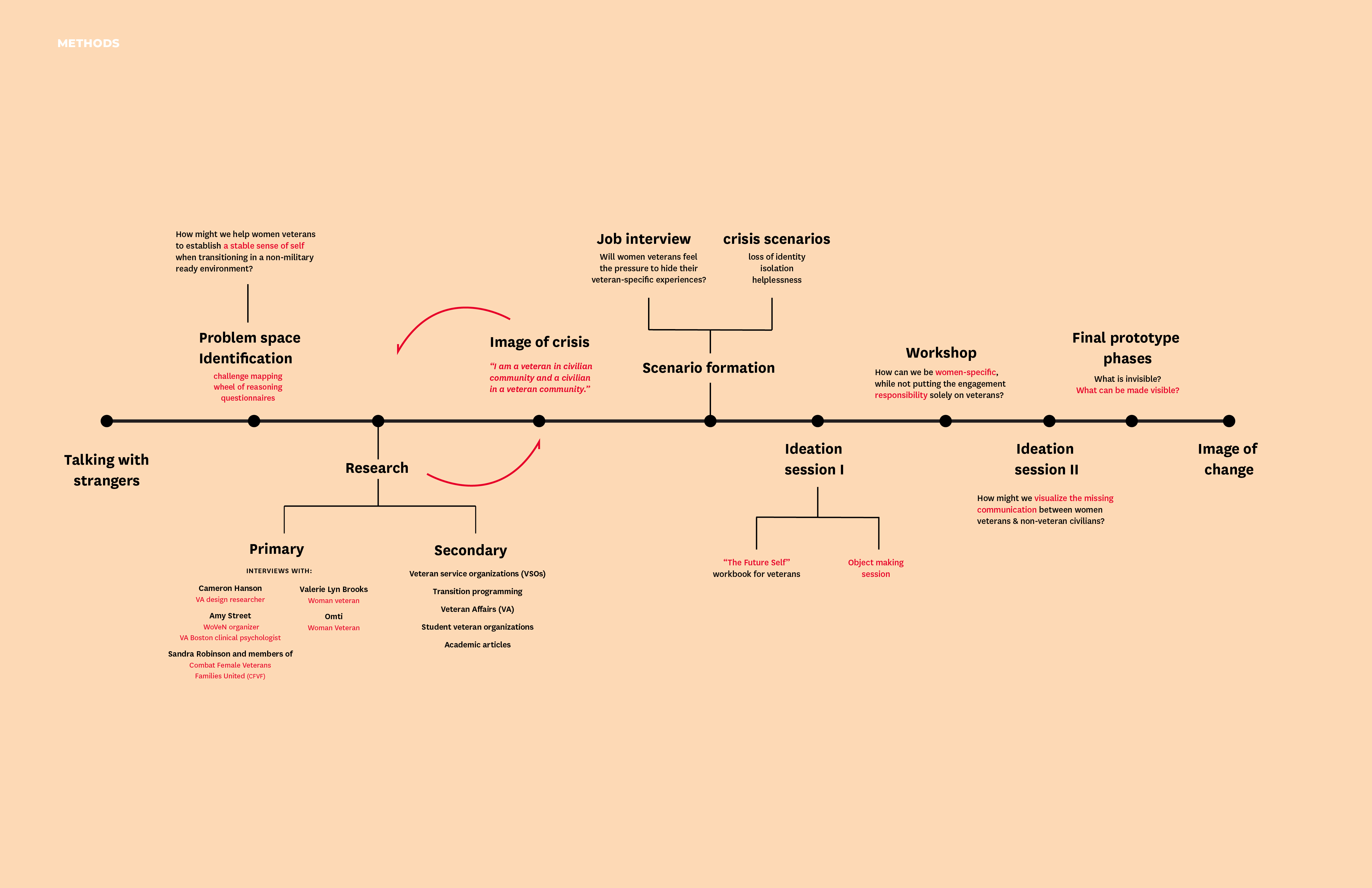

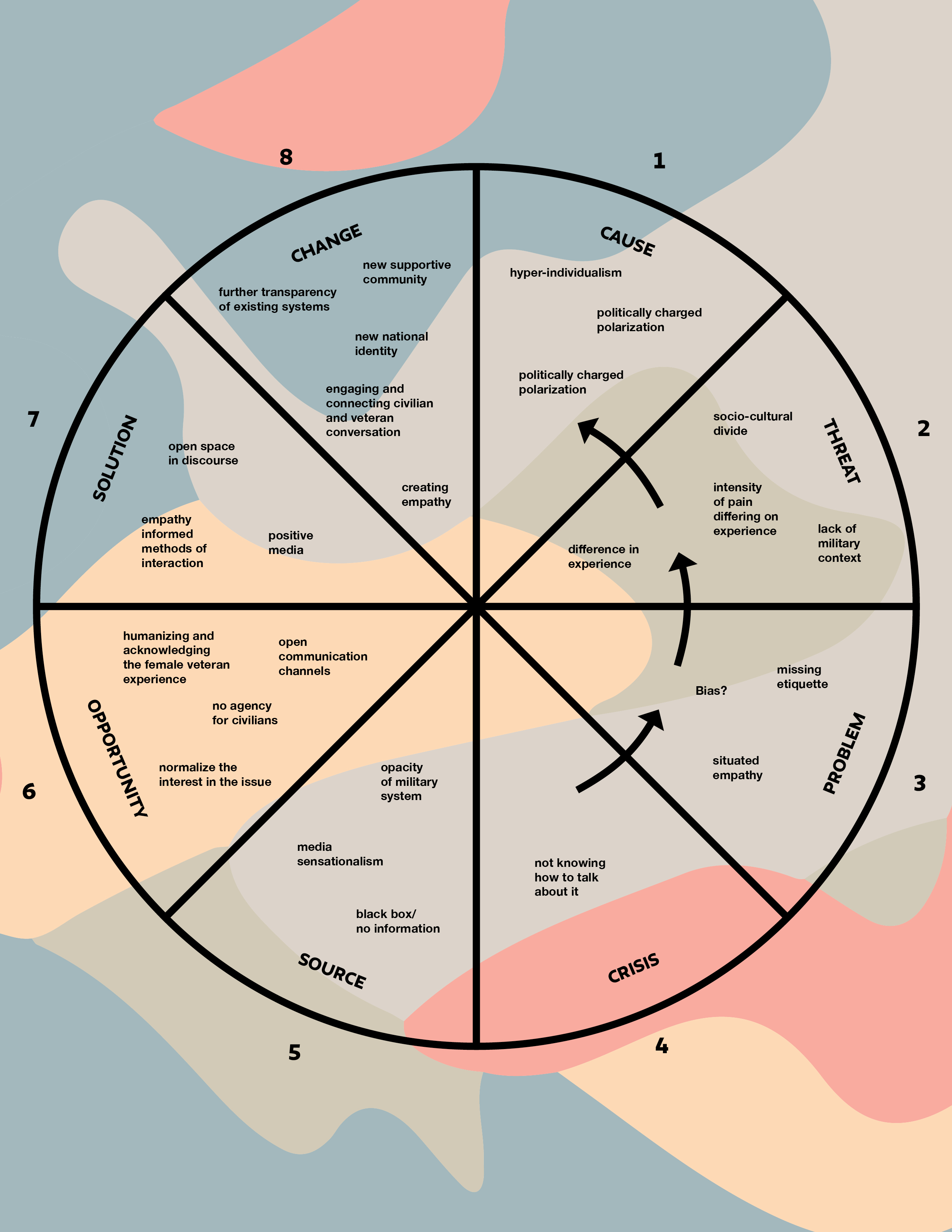

For our project we adopted a participatory form of approach as we engaged with Women Veterans and non-veteran civilians iteratively to get feedback regarding the direction of our approach toward the challenge.

We adopted the core principles of Human Centered Design as we engaged, created, tested and iterated through the process.

Additionally, we defined design principles that would inform our approach towards project in-terms of research and design.

SECONDARY RESEARCH

Our secondary research was guided by the following questions:

“What does the existing transition system in military look like?”

“Which government organizations provide services to veterans?”

“Which VSO’s provide services? And what do they provide?”

“Which organizations are gender specific?”

“What are the services which are gender specific?”

“How does the existing transition system for women operate?“

“What are the different touch points?”

we specifically investigated:

Veteran Affairs (VA)

Veteran service organizations (VSOs)

Transition programs

Student veteran organizations

Academic articles

PRIMARY RESEARCH

As a part of primary research we conducted we approached women veterans who were willing to share their experiences and challenges they faced with us.

PERSONA

Sandra Robinson

and ‘four’ other women veterans CFVFPerspective

VSO organizers

What did we learn?

Shared the troubles of going back to not military ready communities, and how they are ignored as combat WVs back at home. Resentment and misunderstanding from their children, illness and pain due to the lack of women-specific care and equipment during enlistment. Provided us with information on the 5-7 year transition, but current VA program only provides months (see interview document for the accurate time period) Also, pointed out VA services are based on location/state and hence their inconsistency.

Amy Street

WoVeN organizer, VA Boston clinical psychologistPerspective

A VA service provider and VSO organizer at the same time.

What did we learn?

Saw the lack of WV support in VA and formed a national network for WV sisterhood. Also emphasizes on the funding and effort VA is putting on WV-specific healthcare, and are working on it

Omti

Perspective

Women Veteran

What did we learn?

Struggles of having identities both as a WV and a mother `She shared with us how she had to leave the military as she was pregnant. Additionally, her husband is a military officer. Hence, when attending military of civilian gatherings or availing services at the VA, she is often looked upon as a dependant of here husband. She left left out in both communities. Also, the differences between treatment of male and female officers and very visible to her.

ANALYSIS

These experiences became the core that informed our design process. We analyzed these interviews and mapped overlaps on each other. Based on these we created the scenarios which were our images of crisis.

TOUCHPOINTS

We were considering the greater systemic issue of identity crisis faced by women veterans. Communication was an area of intersection and a possible way we could intervene in the system to help create a smooth transition process.

Here, we are not referring to a generic form of communication but communication that was in tandem to their identity as a woman veteran. Due to the existing stigma, women veterans do not reveal themselves in the civilian world unless asked. Society as a whole does not perceive women veterans as existent or it is assumed that they served in supporting roles and hence do not need to thanked.

Due to a lack of visibility and acceptance, women veterans relied heavily on signs that visibly identified them as veterans in the eyes of other people.

“In the military, the uniform and the badges convey everything. I have never had to ask for respect. Also, I always had enough context to start a conversation. Here, I need to build everything from scratch. I am not used to talking about my military experience because I don’t believe they will get what it’s like.”

SYNTHESIS

This statement was our key insight as it brought forth the reason as to why it was so difficult to talk about their identity. The veterans wore their identity and never really needed to discuss about it. The process of engagement is simplified. Just by looking uniform and the batch one could know what battles, they have been in, what their rank was, which platoon they were a part of. We realized the uniform and badges represented more than pride, hierarchy and power. It was also a form of invisible language among them. It is like wearing your experience and respect comes naturally when you know what they have been through.

︎︎︎ How might we visualize the missing communication between women veterans and non-veteran civilians?

Now that we had defined the space of our intervention and its function. We had to create a scaffolding to hold these functions together i.e is an approach method that could help us define our strategy.

We revisited our interviews and this time tries to extract patterns that bubbled in the unspoken conversations. We realized that the approach to conversations varies depending on whom the women veterans were interacting with. Hence, we broke this down into four layers. And each layer is important to building a strong sense of self. We draw from concepts of levels of intimacy in psychology to develop this method.

Open communication at each level would help create a strong support system for women veterans. We designed the approach to each layer of communication through the lens of our design principle of respect & appreciation, trauma informed culture, transparency & privacy and agency restoration.

We revisited our interviews and this time tries to extract patterns that bubbled in the unspoken conversations. We realized that the approach to conversations varies depending on whom the women veterans were interacting with. Hence, we broke this down into four layers. And each layer is important to building a strong sense of self. We draw from concepts of levels of intimacy in psychology to develop this method.

Open communication at each level would help create a strong support system for women veterans. We designed the approach to each layer of communication through the lens of our design principle of respect & appreciation, trauma informed culture, transparency & privacy and agency restoration.

MACROSYSTEM

communication with strangers

“I’m a women veteran, and I served my country with pride. I understand that there is social bias. However, I would appreciate it if you don’t question my authenticity.”

communication with strangers

“I’m a women veteran, and I served my country with pride. I understand that there is social bias. However, I would appreciate it if you don’t question my authenticity.”

MESOSYSTEM

communication with peers, colleagues, etc

“I’m a veteran and can’t always share my experiences. However, if I behave in a certain way you don’t understand, I would appreciate it if you would communicate with me.”

communication with peers, colleagues, etc

“I’m a veteran and can’t always share my experiences. However, if I behave in a certain way you don’t understand, I would appreciate it if you would communicate with me.”

MICROSYSTEM

communication with family, partners and close friends

“I’m a veteran, and I’ve been away. It’s ok that we don’t understand each other right away. Let’s rebuild our

relationship together.”

communication with family, partners and close friends

“I’m a veteran, and I’ve been away. It’s ok that we don’t understand each other right away. Let’s rebuild our

relationship together.”

INDIVIDUAL

This level focuses on the communication of women veterans have with themselves

“I’m proud of being a veteran in the civilian world, and now I’m able to embrace my civilian identity. I accept myself the way I am and am open to sharing my entire identity. ”

This level focuses on the communication of women veterans have with themselves

“I’m proud of being a veteran in the civilian world, and now I’m able to embrace my civilian identity. I accept myself the way I am and am open to sharing my entire identity. ”

DESIGN

TESTING

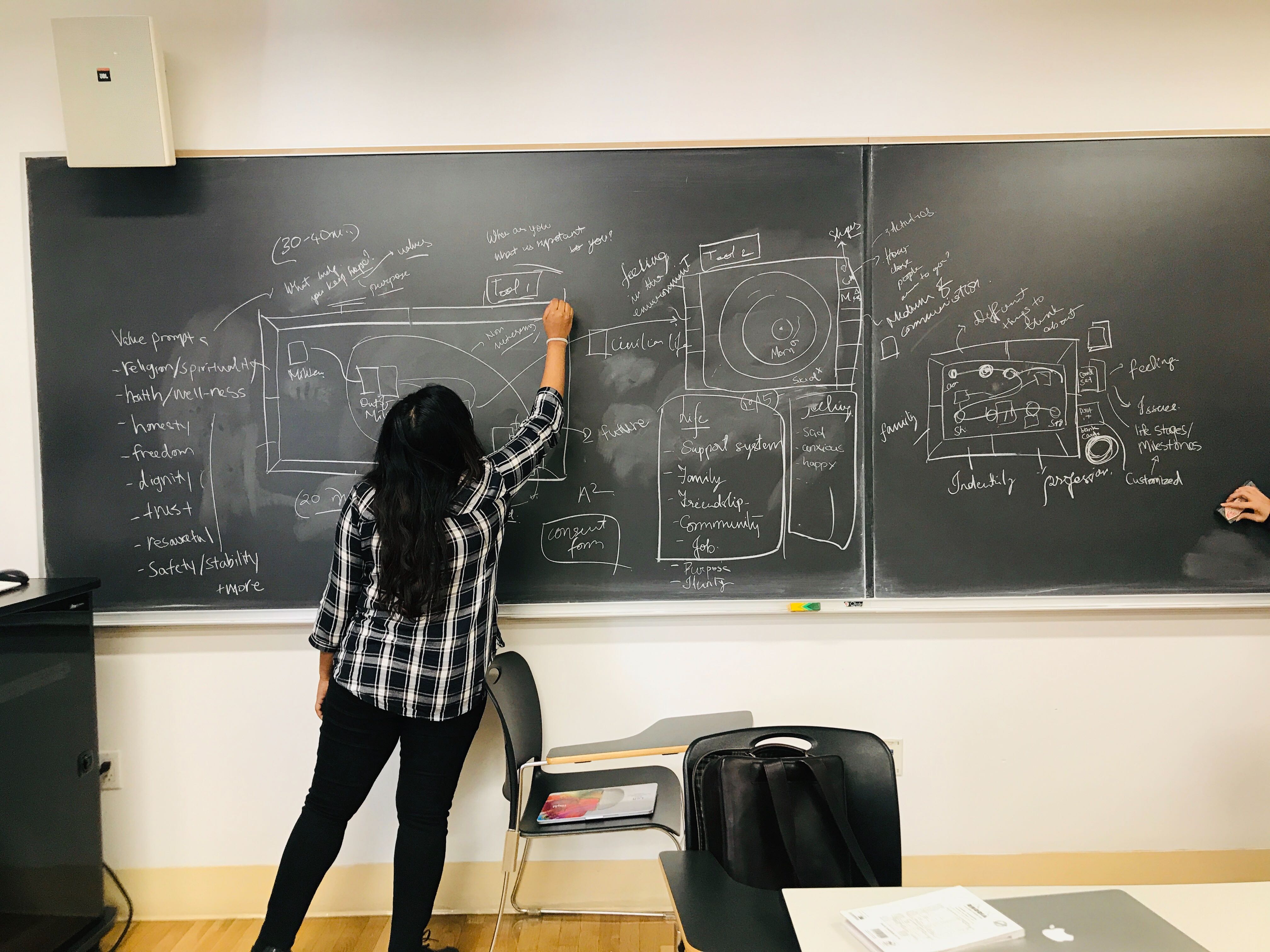

Having created a framework we tested our approach strategy by setting up a workshop. We used this workshop as a provotype to create discursiveness around concepts of intention manifestation and visualization of unspoken words.

The workshop was divided into three parts and was designed to engage both veterans and civilians in-order to test both concepts. Both had a slightly different journey which we guided them through.

The workshop was divided into two different levels, one designed for veterans and one for non-veterans.

FOR VETERANS

Intention

Manifestation

1

Engaging with Narratives

The first step was the introduction of the context and images of crisis we created from our interviews. Then we asked them to share their experiences and the scenarios they found relatable.

![]()

Engaging with Narratives

The first step was the introduction of the context and images of crisis we created from our interviews. Then we asked them to share their experiences and the scenarios they found relatable.

2

Self reflection and hope for the future

Having picked out a scenario they participated in a self-identity exercise where they reflected on their current behaviour and defined what they would like their future self to look like. They defined the image of change as a narrative that captured how the future situation would play out with their changed behaviour.

![]()

Self reflection and hope for the future

Having picked out a scenario they participated in a self-identity exercise where they reflected on their current behaviour and defined what they would like their future self to look like. They defined the image of change as a narrative that captured how the future situation would play out with their changed behaviour.

3

Object Making

Finally, they were asked to determine an object that would be play an important part in the scenarios and would act as a reminder of their intention to change. This object would represent a visual manifestation of their intentions.

![]()

Object Making

Finally, they were asked to determine an object that would be play an important part in the scenarios and would act as a reminder of their intention to change. This object would represent a visual manifestation of their intentions.

NON-VETERANS

visualization of unspoken words

1

Engaging with Narratives

The first step was the introduction of the context and images of crisis we created from our interviews. Then we asked them to select a scenario that they felt strongly about.

![]()

Engaging with Narratives

The first step was the introduction of the context and images of crisis we created from our interviews. Then we asked them to select a scenario that they felt strongly about.

2

Self reflection and hope for the future

Having picked out a scenario they participated in an identity exercise from the perspective of the non-veteran civilian in the scenario. They reflected on the current behaviour and defined what they would like the future self of the civilian character to look like. They defined the image of change as a narrative that captured how the future situation would play out with their changed behaviour.

![]()

Self reflection and hope for the future

Having picked out a scenario they participated in an identity exercise from the perspective of the non-veteran civilian in the scenario. They reflected on the current behaviour and defined what they would like the future self of the civilian character to look like. They defined the image of change as a narrative that captured how the future situation would play out with their changed behaviour.

3

Object Making

Finally, they were asked to determine an object that would be play an important part in the scenarios and would act as a reminder of their intention to change. This object would represent a visual manifestation of their intentions.

![]()

Object Making

Finally, they were asked to determine an object that would be play an important part in the scenarios and would act as a reminder of their intention to change. This object would represent a visual manifestation of their intentions.

INSIGHTS

The veterans shared emotional moments with us. This helped us realize the importance of the entire process as opposed to creating just an object.

Examples of many objects were generated, however, we realized the need for homogeneity of the object to make them more representational for all women veterans.

We decided that we needed to make the entire workshop more gender specific.

IDEATION + PROTOTYPING

Based on the insights we gathered from our workshop we concluded that the prototype should include two components.

We created rough sketches of prototypes and we tested them conceptually against the images of crisis and deliberated on how it played out in each case. Additionally we got feedback from our guide and peers. Based on which we came up with the following functional guidelines for our prototypes.

Prototype 1

The bracelet would have multiple beads. One represents a part of their veteran identity and the rest represents the component relevant to that - physical and mental health, emotions, intentions, etc.

Prototype 2

A bracelet or necklace with detachable parts. The veterans would give these parts to their trusted civilians. It would also include a stamp which you help veterans stamp safe spaces.

Prototype 3

A necklace which included a morphable shape that would be 3D printed based on the questions they answered of self-identity.

INSIGHTS

WORKSHOP

The workshop has to create a platform to work through the various levels of communication. It has to be engaging and reflective in nature. It has to be accessible to all women veterans in-term of location.

OBJECT

It should be representation of identity for women veterans for veterans and civilians alike. It should be a conversation starter. It should be portable. It should something that would blend in with ones attire and yet stand out.

RESULT

CONCEPT

Our final proposal is a program called LINK

We designed the program to serve as a bridge between women veterans and non-veteran civilians. It directed toward the women veterans. It is positioned right after the TAP program in the transition stage to help engage in conversation about identity and interaction with non-veteran civilians. It is a guided process that could be facilitated either in peer groups or can be taken online through digital medium.

NECKLACE

We imagine the necklace to a representation of the community of women veterans for both veterans and non-veteran civilians.

The design of the necklace is inspired by the circles of communication.

It has 6 components, the four pendants, the chain that ties together the components, and the hook that connects the pendants.

Women veterans assembles these components to create the necklace themselves as the progress through the LINK program. This helps them associate each component with a deep meaning.

PROGRAM

During a program over 8 weeks women veterans follow a step-wise guide to help them think about their identity and role in the civilian work after military.

IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY

IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY

For our next steps we will first need to get feedback from the women veterans and service providers who participated in our design process. We will need to improve the content for our Journal of Change and refine LINK’s program structure.

Secondly, we want to pilot test the program. For which we intend to collaborate with the Combat Female Veterans Family United (CFVF), a VSO that we have been in contact with for our primary research. They have been very cooperative and generous to share their experiences and insights with us. They currently have a transition program in place.

We intend to approach Sandra Robinson, CFVF’s founder to help us pilot test this program as a part of their transition program module. We are very excited at the possibility and look forward to seeing what our project might manifest into.